Disclaimer: I am on the editorial advisory board of Mainsheet, the subject of this review. My experience is that editorial advisory boards are simply lists of names intended to add a certain credibility to the proceedings, rather than people sought out for actual advice. (I once discovered that I was on an editorial board by chancing to notice my name on the journal’s masthead.) To its credit, and my surprise, Mainsheet’s editorial team—the people who actually solicit, edit, and send articles out for peer review, and produce the physical product—have gathered its advisors in several Zoom meetings to get our take on such generalities like whether to have themed issues. I have otherwise had no input into the contents of the journal

The field of maritime history is served by a number of fine academic journals and popular magazines, among the best known being The Mariner’s Mirror, International Journal of Maritime History, International Journal of Nautical Archaeology (IJNA), The Northern Mariner/Le marin du nord, and Sea History. Between them they cover a wide range of specialties, and it is reasonable to ask whether there is any need for a new one. The first issue of Mainsheet—available in print by subscription (which I recommend) or free online—published by Mystic Seaport Museum, has allayed whatever doubts I had.

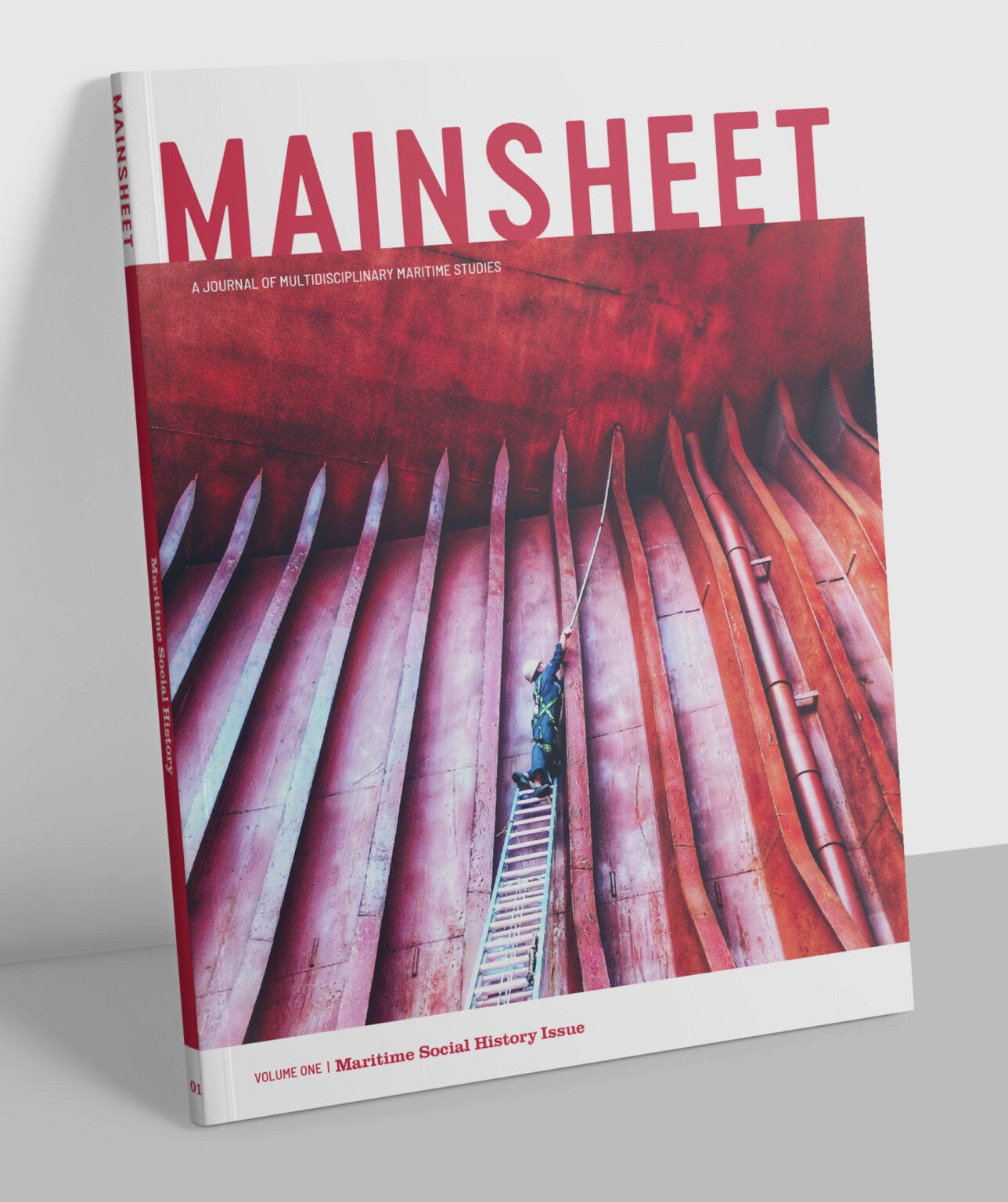

Most obvious, the production values are very high. The journal is perfect bound, printed in four-color throughout, and the paper is glossy but not shiny. One improvement that could be made is a biding that lays flat when open, the better to enjoy the lavish illustrations, which run the gamut from archival and museum images to contemporary photographs. The cover illustration depicting a sailor precariously painting the top of a cargo hold comes from a feature entitled “Unsung Heroes: The Invisible Workforce Powering Global Trade,” which showcases the work of sailors who participated in annual Life at Sea photography competitions first sponsored by the ITF Seafarers’ Trust at the height of the COVID-19 crisis in 2020. (The trust is a British charity funded by the International Transport Workers’ Federation.) With titles like “Sea Witch,” “Dirty Hands and a Sweaty Face are the Signs of Clean Money,” and the cover shot’s “Keep reaching your dreams how high it may seem,” these capture the solemnity, humor, variety, and challenges of the working seafarer’s life with an intimacy that outside observers do not, and without any sacrifice in quality.

Mainsheet’s text-based articles include both peer-reviewed scholarship and features, as well as poetry and reviews of books and museum exhibits. There are also listings of upcoming exhibits and academic opportunities and happenings (although it is not clear how helpful such time-sensitive announcements are in a biannual journal), and an obituary of Bill Pinckney, the first African American to circumnavigate the world alone and who later served as captain of the Amistad.

For non-academics, the distinction between peer- and non–peer-reviewed articles can be subtle, especially here. Akeia de Barros Gomes’s Perspectives piece, “(Life) Cycles, (Ocean) Currents, and (Ancestors’) Rhythms: Dawnland Maritime Histories through Indigenous and Black Voices,” serves as a useful introduction to Mainsheet generally and to this issue’s theme of Maritime Social History in particular, the unwieldy title notwithstanding. In it she reflects on connections between West African and Indigenous North American conceptualizations of “waterscapes as seamless intersections of land and water that create social, cultural, and spiritual understandings” and explores how they wove these understandings into “enforced concepts of Christianity.” Her focus is on the survival and transmutation of these beliefs among Indigenous and people of African descent, and she calls upon non-BIPOC people to stop forcing “global maritime narratives into a Western frame.”

De Barros Gomes’s sensitivity to this subject is due partly to her own experience as a descendant of both enslaved African and free Cape Verdean arrivals to the United States as well as to her training as an anthropologist. With respect to the latter, she is explicit about her approach to articulating what she has learned:

I will share some knowledge about this maritime history that has been shared with me (knowledge that I have permission to share) from African, African American and Indigenous community members. Of course, the Indigenous stories are not mine. They are histories that have been told to me for the purpose of sharing and education. And I have been entrusted to relay these stories truthfully, respectfully, and sensitively, with humility and in friendship.

Her concern is a valid one and shared by a growing number of people across a range of disciplines, including historians, who are increasingly urged to recognize that Indigenous communities are custodians of their own knowledge—if only because being heedless of their agency can impede research agendas.[1]

De Barros Gomes’s Perspective piece is in dialogue with several peer-reviewed articles, especially Jason R. Mancini and Silvermoon Mars LaRose’s “The Narraganset Chief, or the Adventures of a Wanderer’: Recovering an Indigenous Autobiography.” This recounts the rediscovery and offers of analysis of an obscure but riveting 195-page memoir published anonymously in 1832. The authors attribute the authorship to Charles Lansing, a peripatetic mariner who was the child of an unnamed, possibly Oneida, father and a Circassian mother (from the Black Sea coast east of the Sea of Azov) who had married as captives in Algiers. He learned of his descent from Narragansett sachems only after meeting his father—for the first time in twenty years—in a Spanish prison where they were held for fighting against the forces of Joseph Bonaparte.

The article is a fruitful mix of a scholarly approaches to the text and more personal commentaries on “the process of recovery, interpretation, and reconnection” by Mancini, former executive director of the Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center in Ledyard, Connecticut, and LaRose, a member of the Narragansett tribe and assistant director of the Tomaquag Museum in Exeter, Rhode Island.

Several other articles are devoted to often overlooked maritime cultures, notably Kevin Dawson’s “Liquid Motion: Reimaging Maritime History through an African Lens” and Alison Glassie’s “Our Lady of the Workboats: Solidarity and Spirituality on the Bay of All Saints,” about Jorge Amado’s modernist novel Mar Morto [The Sea of Death, 1936]. More familiar aspects of maritime history also get their due like Timothy D. Walker and Caroline C. Ummenhofer’s “Extracting Global Weather Data from New England Whaling and Portuguese Navy Logbooks (1740–1960)” and Alice C. M. Kwok’s “Dragon Ships to the Dawnland: Eugène Beauvois [1835–1912] and the Vinland Viking Expeditions,” which offers a fascinating take on how historians can use history not to ask questions about the past, but to shape the present through selective narrative.

If what’s past is prologue, and what to come in Mainsheet’s discharge, the future of maritime studies is in good hands.

For information on submitting articles, click here.

[1] Paleo-geneticist Jennifer Raff makes a strong case for acknowledging the prerogatives of Indigenous communities in Origin: A Genetic History of the Americas (2022).